why can’t we say what the soldier said?

Regimental honours for Cpl Nathan Cirillo, Ottawa National War Memorial, October 24, 2014

October 24, 2014

We had a weird week in Canada. On Monday, a slightly unhinged convert to Islam followed the lead of ISIS and used a car to attack Canadian soldiers. One died.

The next and perhaps weirder thing was that no-one wanted to talk about it. Like a ballerina on an ice flow, the starchily correct Canadian media-types minced about on toe shoes avoiding the impolitic facts of Martin Couture-Roulleau’s religious affiliation and political agenda.

That lasted until Wednesday, when the Fall torpor of our quiet capital city exploded in streetside mayhem, as a very unhinged convert to Islam attacked our soldiers, our most sacred shrine and our Parliament. We watched it from our office windows, in “lock down”, and we watched it on big TVs and phones and computers and we made sure our own were safe, and we stayed indoors. Terror had come to Sleepy Town. One soldier was slain, a near gun-massacre in Parliament was averted by a sure shot public servant, the PM was hidden away and his caucus barracaded the doors with furniture and fashioning flagpoles into spears.

And they say nothing interesting ever happens in Ottawa. More interesting things were to come in the next two days, including visibly shaken public addresses by our three political leaders and the next day, the unthinkable sight of Harper, Mulcair and Justin Trudeau hugging on the floor of the House of Commons. And a hush fallen over the citizenry, stunned to silence.

And beneath it all, the dark and brooding truth of a young man dead, his handsome smiling face shining out like a beacon. Killed at the foot of the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, guarding that ancient victim of a long ago war. Guarding him unarmed, of course. This is Canada.

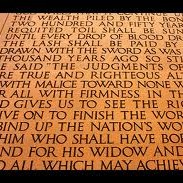

A colleague and I went for a walk to the War Memorial this afternoon and came upon the regimental honour guard ceremony for Corporal Cirillo. The pipers sent out a plaintive tune. The crisp blue uniforms stood trim and strong in the warm sun. They marched, they turned, they saluted. The assembled public, which grew and grew, was silent, their only movement the lifting of cameras to catch a snapshot of the ceremony over the strangers’ heads. The crowd was riddled with security types, tall, stiff and tense, their tiny single ear buds burning with clipped observations and orders. The Prime Minister arrived, to an unusual spontaneous burst of public applause – I think people were just impressed to see him out there, right there on the spot Nathan died, in plain sight of a thousand windows where assassins might have lurked.

As days unfold from here, we will likely watch the thin pastiche of political amity fall apart like Fall leaves, crumbling in our fingers, colours lost to dust. There are legitimate issues – the seemingly spotty security which permitted an armed maniac to come within feet of slaying our First Minister and other Parliamentarians – that’s worth talking about. The security services are floating ideas to preventively arrest the likes of Rouleau and Bibeau, an idea which I think most Canadians will consider over-wrought and over-reaching. And there is the unasked and unanswered question of how it is native-born young men can, by virtue of their frailties, be so quickly seduced into a lunatic ideology of death. Taking orders over the internet from Camp ISIS, and all that. At the same time, we will hear about how nice Muslims are and how Islam is a religion of peace – and at the same time we will witness the sorry spectacle of Muslim Canadians apologizing for what some basement-dwelling convert creeps did in the so-called name of their faith.

What will come of all the chatter? What will the murder of Nathan Cirillo and the assault on our national institutions bring us? Stupid forms of “security theatre” will be adopted as a way of making people feel safer, without making people actually safer. And I fear that if we are not very disciplined about it, and we aren’t likely to be so disciplined, it will devolve into the usual right-left-right-left debate about security versus liberty, transparency versus privacy, loyalty versus diversity. God knows I feel myself devolving into that.

I love my country. I love that my daughter has the best chance of any girl, any where, any time in the whole history of this beautiful misbegotten world, to choose her own life. I love that in the cities, people don’t look alike, that their tongues are thick with accents and their plates buried in different foods. I love that the same families have farmed the same countryside for a century and are just about the best raisers of food on the Planet Earth. I love that we have come close to breaking and didn’t (although I didn’t love it at the time). I love three seasons and can tolerate the fourth one, the one that eats up about half the year. I love that I’m walking home soon, down a street full of shops and shoppers, past a football stadium jammed with jolly fans, over a bridge and down a dark leafy street. I love that my mom, who had nothing but a heart condition and an iron will, was given welfare cheques to keep us alive while we scrambled to make our own better life. And that we could make our own better life. That I could get jobs as a lad, and as a young man, and save and with the taxpayers’ considerable help, stay in school for a long, long time. That I could come out of school and pay all those taxes back, and then some. I love that the money I make and return to the country goes to some other single mom.

I love that we have different ideas and faiths and foundations inside us. I love that we are strong and brave enough to live that way, unthreatened by it.

But we are threatened by something. We are threatened by complacency, by the pleasant notion that everyone can be himself or herself without regard to where they are, who they live amongst, what they have inherited and what they must bequeath. Freedom comes at a cost, and the absolutely minimum price each of us must pay, surely, is to pledge loyalty to that freedom. To swear before God or Allah or whatever you believe, that to live here means to defend our civic values and democratic institutions.

We almost never ask that of Canadians, unless they are new citizens or hold certain public offices – or we are members of the Forces – unless we are in those roles, such words as “allegiance” would never enter our ears or spill from our mouths. And that silence is a dangerous, senseless thing. For he who never says it, never has to think of it.

It can be said, fairly, that Rouleau and Bibeau probably didn’t commit acts of terror because they weren’t asked to pledge allegiance to their country every day as boys. Maybe not, but one thing is for sure – they weren’t asked to pledge allegiance to their country every day. Any day, for that matter. Ever. Because we don’t do that. We milk the cow, but not only don’t we feed the cow, we don’t even say nice things to the cow. We just milk it.

But why not dedicate ourselves to our country? Why not declare our loyalty? Not to any particular government or any particular policies, but to the bright burning idea of liberty that many, many Canadians – two more this week – laid down their lives for. Why weren’t little Martin and Michael taught to put their hands across their hearts and stare at that red and white flag and swear, affirm, whatever, that they would be true to their country? Why isn’t it IMPOSSIBLE to go to school and not learn that, relentlessly and ceaselessly and exhaustively?

Words matter. When you finally say “I love you” to someone, those words matter. They matter to say and they matter to hear – the mere uttering of them changes you. Think about it – you know that’s true, and that’s why you don’t say it very often. Because words matter. We learn from what we hear and what we say, particularly as small children. But we say nothing of love to this country. How is it that Canada, which poured the blood and bone of men and women into the muddy graves of two European wars and the sands of Asia, never hears those words? How is it that the very idea of pledging allegiance to the nation is alien and, for many, utterly objectionable?

I don’t understand that. I don’t understand why we don’t acknowledge our greatness as a nation and proclaim it, not arrogantly or boastfully, but honestly. A greatness we inherited and are part of, a greatness we must at times serve – if only with a few words. And maybe more. What happens I think is that we don’t realize where we are, we don’t realize the greatness we are part of, so we don’t realize how goddamned grateful we should be. We are less than we should be as people, because we are so inert and passive as citizens. Canadians belong to something magic and precious, carved out of unwelcoming soil and defended every day. No one teaches us this, no one asks us to acknowledge this. And the country should.

An argument against this is that words can be hollow. People lie. You might make an oath or pledge a condition of school or work, and people will just say it without meaning it. So what’s the point?

The point first, is that most people wouldn’t be lying. They would mean it. Or they would be learning, and reminding themselves too, of what they owe their country. Why take that opportunity away from people to spare those who aren’t loyal? And if someone can’t honestly declare his loyalty to Canada and its values, let them be honest. Or let them be liars. Who cares? They’re traitors anyway.

Ours is not a martial country. We are horrified by violence, shaken to hear gunfire in the chapel of our democracy, heartbroken that two men could be cut down on our own soil, simply for wearing the uniform. But to be peaceable is not to be stupid; to be forgiving of each other’s differences is not to be indifferent to an enemy spirit. Patriotism can be ugly and hazardous, but it can, if handled gently, be beautiful and right. There isn’t a country on earth more likely to get it right than careful, considerate Canada.

We are told that Nathan Cirillo loved his son, and as a father I believe that he did. We are told too that Nathan Cirillo loved his country – and would say so to his friends and fellow reservists. He loved his country. He took the Oath of Allegiance. He said it. And he was proud to stand there, silent and still, guard to the Unknown Soldier, right up to the moment a traitor cut him down.

So here’s the question: why can’t we say what the soldier said?

Because maybe if we said it, we might know better why we should.

Bravo David. Find the cost of Freedom.

mobile mike

LikeLike

Pingback: A mask tells us more than a face | Think Anew, Act Anew