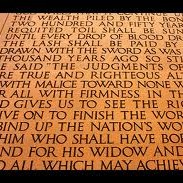

Oh say can you see, the ties that bind?

The first graphic depicts the intensity of Republican and Democratic votes, as cast and counted in the 2012 Presidential Election. The second shows population density.

The larger red and blue zones fall within the states that you might expect, but what we also see is that there is a distribution of support across every state. There may well be different “cultures” in Massachusetts and Arkansas, but there lives within each of those states many people who are not prepared to vote for President, based on the dominant culture.

When I look at this map, I am struck by something that had not occurred to me before: the closer you live to your neighbour, the more likely you are to vote Democratic.

This is just an impression, but I tested it in one place: Texas. The State of Texas is perhaps the most reliably modern Republican state, not having supported a Democrat since son of the south Carter in 1976 (they dumped him in ’80 and never went back to the Dems). In 2008 Texas gave a fat margin to John McCain, resisting Obamamania, and did it again for Romney last week. Yet Austin, with a relatively small African-American population, has been known as the “people’s republic” and has been liberal Democrat for years, even before the growth of its Hispanic population. My guess is, the thesis will hold up generally if tested further. There are red streets and there are blue streets.

The recent New York Times opinion piece citing values as the basis for votes, not demographics, certainly rang true. But “values” do not exist in isolation – they emanate from a person’s whole lived experience, including the proximity of neighbours, which itself begets the use of public facilities over private ones (the cafe, versus the kitchen), and is inextricably tied-into community reliance upon shared services (the subway, versus the SUV). Without even consciously choosing it, people may drift into a value set, or become influenced by one, simply through the manner in which they complete day-to-day experiences and transactions.

It is still possible, in the middle of a suburban acre, or on a country hilltop (where I sit, watching the sun rise) to believe you are “alone”, that the government is an unnecessary burden. If people do not see the manifestations of state action in their lives, except as a tax collector, they will almost certainly come to bitterly resent the taking, and to resent those who rely upon the public treasury for services and assistance. And it is not imaginary to believe, up on that hilltop or on that acre, that much good emanates from private action – because many visible goods do arise from volunteerism, charity and church.

But the refusal to acknowledge the value of the state is, in itself, a state of denial. The veterans we remember today, on November 11th, didn’t represent Lumberton County, Texas or Ste-Adele, Quebec; they were American and Canadian troops. The clean water in the lake below me is not an accident of Providence or merely a result of restrained use by neighbours (although that matters), but also of a regulatory framework. The money in your bank account may be your money, but the currency is created by an organ of government, and your bank itself is regulated and protected by the state, so that no-one can just walk in and snatch it up while you’re sleeping.

Indeed, the whole concept of “law and order” is possible only through the collective action we call government. The personal liberty we each cherish survives only because armed men and women, some of them driving around in police cruisers today, some of them riding in armour-plated vehicles through Afghanistan, many of them buried in cemeteries and fields around the globe, have defended that liberty. The other night I dined at a banquet table populated with old soldiers and young officer cadets. These are among the most impressive people I’ve ever met, demonstrating a zest for duty and a passionate comradeship that seems utterly absent in civilian life. They all work, or used to work, or will work, for the government.

My thesis, perennially, is that individual freedom and accountability is the highest and most moral form of life. The erosion of that liberty is a sin and threat to every one of us. The individual lives within her own skin, should exercise as much choice as she can possibly manage, and should suffer as little coercion as possible. But freedom comes at a price, and it is not guaranteed, and progress is not permanent. We purchase that liberty through our efforts to restrain those who would steal it, and by restraining those who would abuse it through an inordinate exercise of their physical, psychological or economic power. At the same time, we encourage the exercise of liberty through public support for the weak, the insecure, the poor and the powerless. Employees of the state – the soldier, the cop, the teacher, the social worker – are all defenders of liberty.

Perhaps it is easier to see, in the crowded and jostling streets of the city, how bound together we are. Perhaps when we climb in our cars and roll outwards, into the suburbs and exurbs, or around the countryside, we can forget the degree to which we are intertwined and interdependent. Inside the glass bubble of our vehicles, with radio stations fixed on the voices of like-minded souls barking into microphones, bleating mantras that reinforce our imaginary isolation, we become detached not only from our fellow-man but from reality.

That is not a fair characterization of every conservative, but it is fair of too many. A true conservative understands how we got here and mourns the fragility and loss of traditional ties, mostly private and personal and communal, which nourish life in so many ways. She distrusts the seeming replacement of those ties with artificial, forced and legalized relationships imposed by the state. A conservative knows, correctly, that an over-reaching state can diminish our liberty as much as enable it (perhaps more) and she would rather we err on the side of autonomy, rather than communal action. That is fine, so long as she knows her autonomy is being paid for by communal action.

I am left to wonder, as I look at the maps of where Americans live, and how Americans vote, whether the amount of space surrounding a person simply makes it harder for her to see, some of the ties that bind: the public library, the city park, the man fixing the pothole, the crop insurance, the social security cheque which keeps a neighbour alive. How is that someone can turn a tap, and take a glass of clean water, yet never think about the countless people – including the taxpayer who lives next door – who made it possible? Out of sight, out of mind.

So the trick is, I guess, to get folks to look out their windows. Lest we forget.